This text is written by Professor Kari Holdhus, who is a researcher in the FUTURED WP3. She introduced the topic of relational pedagogy to the FUTURED #TextImmersion group, which led to this blog post.

Relational educators often approve of thoughts stemming from psychologist Kenneth Gergen’s 2009 book Relational Being, of which he writes:

After placing the tradition of the individual or independent self under critical scrutiny, the initial attempt was to generate an account of persons as inherently relational. If the origin of all meaning lies within collaborative action (co-action), then not only does the individual self but, indeed, all intelligible action find its origins in relationship. From this standpoint, all psychological process can then be reconstructed as relational process. These conceptions were then linked to practices of research, education, therapy, and organizational change. Finally, their relevance to morality and spirituality were explored.

Kenneth Gergen, 2009, p. 280

Within education, the Appreciative Inquiry (AI) education approach can be linked to Gergen’s writings. AI represents an educational strand that seeks to emphasize and build upon strengths and positive resources in people and groups, often utilizing 5 Ds as a vehicle for educational activities: Define – Discover – Dream – Design – Deliver. AI is a social constructivist approach that builds upon student resources as well as student hopes, dreams and possibilities, where the educator needs to research, acknowledge and build upon student resources. This necessarily demands educational relations that appear more profound than in i.e., instructional or encyclopedic teaching.

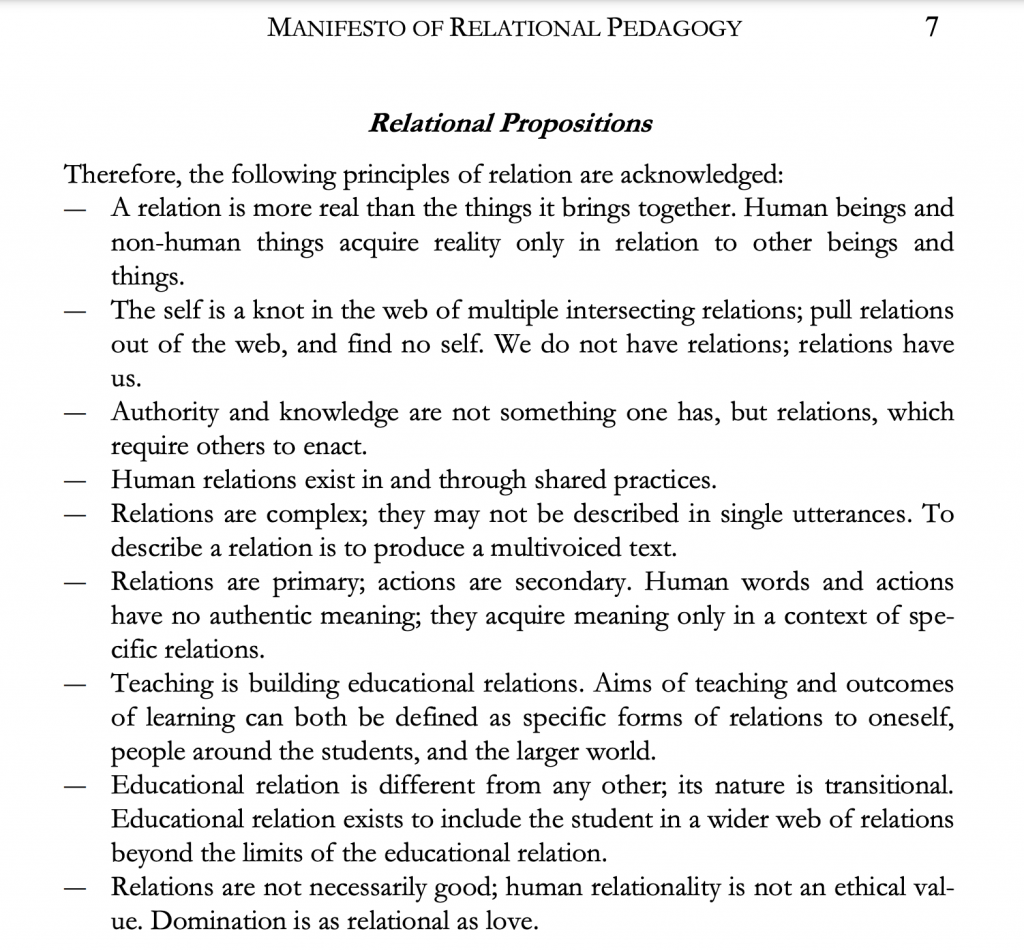

Bingham & Sidorkin’s 2004 edited book “No education without relation” (Full text, enjoy!) emphasizes and enhances Gergen’s relatively sparse focus on education in his 2009 book. The volume opens with a joint chapter and a manifesto written by all contributors:

Relational education strongly dismisses education as something individualized and competitive. Instead, its proponents point at the multi-voiced, ambiguous and messy reality of educational situations, where there are plentiful occasions of conflict and aporia, and where trust and reciprocal respect needs to permeate communal classroom activities. Driven by engagement, following up on the 2004 anthology, Alexander Sidorkin has summoned colleagues to action, opposing accountability and standardized testing as educational benefits. This has resulted in Relation-Centered Education Network, active with conferences, discussions and writings. The network also hosts a Facebook group. Both at the RCEN website and in the Facebook group, recent articles of relational education steadily appear.

In Gert Biesta’s contribution to No education without relation he writes:

- … education is basically a relationship between an educator and the one being educated. But in order to understand the precise nature of the educational relationship, we should take the idea that education consists of the interaction between the teacher and learner absolutely seriously.

- We should take it in its most literal sense. If we do so, it follows that education is located not in the activities of the teacher, nor in the activities of the learner, but in the interaction between the two. Education, in other words, takes place in the gap between the teacher and the learner. (Biesta, 2004, p. 12/13)

Biesta thus appoints “The gap” between teacher and student, which often has been regarded as a problem, to bear possibilities for educational transition and transformation.

In later work, Biesta deepens his views on relation – discussing three aspects of education, namely Qualification: Knowledges and skills, Socialization: Participation, inclusion, democracy, and Subjectification: To become and be oneself. In subjectification there lies uniqueness, which contains the understanding of to be and act in the world as relating to others. Thus, pupils need to be granted the opportunity to education and at the same time come forth as unique. Inclusion is a core value in this. However, according to Biesta, this is a troubling notion, because the unit to be included in always must be defined by someone or something in power. (Biesta, 2007). Therefore, Biesta suggests incalculation as a more suitable approach. As long as you’re here, no matter how different you are, you belong.

In which ways can relational education be of importance in general music teacher education? In her article on Pedagogical Relational Teachership (PeRT), Ann-Louise Ljungblad suggests three main teacher competencies: Relation, Pedagogic approach and Leadership, and she appoints the relational components to be the most crucial. (Ljungblad though emphasizes that relational competencies can be learnt and trained). Teaching has to be value-based instead of evidence-based. This stance is ontologically grounded in the idea of humans always sharing their social living space with others. It is also based on the idea of humans as relational “beings” and education as relational processes. The teacher-student-relation thus must be based on pluralism and acknowledgement of difference. In such a relational environment a space for the students to shape and nurture their own voice can emerge.

When studying these relational texts, I relate them to music (teacher) education. It is the idea of complexity and pluralism paired with subjectification that especially appeals to me. Discussing access and subjectification, a relational approach can function acknowledging towards exploring student resources. Such resources may be present, however overlooked by systems and standards in music education. This resource-oriented relational approach doesn’t necessarily mean that student wish or taste always should be foregrounded as a bearing principle in music classrooms. It is, however, my belief that a relational approach can function as a resourceful grounding for more or less teacher-led educational activities. Music education is maybe more profoundly culturally imprinted than many other school subjects, and this can evoke educational foregrounding of some musics as more valuable than others.To some degree, educational activities in music still are based on such power-based and culturally grounded discursive definitions. Thus, in my view it is upon time to explore student resources and knowledges as a relational basis for choosing what to teach and how to teach in music.

References

Biesta, G. (2004). “Mind the Gap!” Communication and the Educational Relation. Counterpoints, 259, 11-22. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/42978490

Biesta G. (2007). “Don’t count me in” – Democracy, education and the question of inclusion, Nordic Studies in Education/ Nordisk Pedagogik, 27 (1), 8-29.

Bingham, C., Sidorkin, A. M. (eds.)(2004). No Education Without Relation. In Counterpoints, Vol. 259. Peter Lang.

Gergen, K. J. (2009). Relational being: Beyond self and community. Oxford University Press.

Ljungblad, A.L. (2019) Pedagogical Relational Teachership (PeRT) – a multi-relational perspective, International Journal of Inclusive Education, DOI: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1581280